by Liquid Music blog contributor Trever Hagen

October 11, 2018

11.15am

Los Angeles

I pulled up to Dimitri's home-away-from-home a few minutes earlier than our scheduled meeting. I intended to be right on time for this interview and not let the Los Angeles traffic sabotage an ever-so intriguing opportunity: to have an hour of time with Dimitri Chamblas and Kim Gordon to discuss their upcoming performance for Liquid Music. Moreover to speak with people who have so boldly presented their voices was a chance to learn something. Dimitri and Kim—the former a decorated French dancer and choreographer who has just taken up the role as Dean of CalArts and the latter a house-hold name for anyone interested in rock music in the past thirty years—will perform an improvised movement and sound duet on March 4-5, 2019 at the American Swedish Institute in Minneapolis.

With ten minutes to spend before the interview, I took a short walk around his neighborhood in Silver Lake. The bio-diversity, seemingly-secret homes, hilled driveways are such a striking difference to Minneapolis's wide roads and prairie gentle slopes. Discoveries invigorate the imagination: what is the sunrise like in this cul-de-sac? What is daily life like on this street? The birdcalls betrayed their city living. The dark green palm canopies gave life to an adobe-colored city that has as much mystery as it has smog, both entities hiding in plain view. It is the kind of mystery that emerges in heated tropical pauses.

As my walk looped back to Dimitri’s spot, Kim had just pulled up. We walked in together to Dimitri's modest home. They greeted each other as if they hadn’t seen one another in some time. As Dimitri poured some tea, he spoke with enthusiasm about the dances from India he was studying and their engagement of the facial expressions – intriguing content of that form from that place. We stumbled into a chat about nutrition. Kim had just come from a weightlifting session while Dimitri spoke about the psychology of nutrition. It was a curious conversation – one where everyone was curious to know more about what each had to say about some tidbit of information about health – ancient medicines, super foods, new stretches. It seems the owner manual for the human body is a text that is passed down like this – through reflection on your body, mis-steps, risk management, prevention, cures. Through a reflection on your everyday routines.

Dimitri Chamblas: For nutrition you have to figure out what your day is going to be like, because it is not the same recurrence. Nutrition must be adapted to what your day is going to be. If you have a whole day of rehearsal you won't have the same meal as if you were just resting. You know? What is not often considered is the variety of your everyday life. So for like diets and nutrition "If you do this it is going to be great for this and that" – yes, but my Monday is not the same as your Monday. If you do a whole night or a whole week of some crazy physical activity or whatever it is how you adapt to your life. Not the opposite. Not adapting your life to something that is dictated that you should do.

From the start of our conversation it was clear that the boldness of any artistic voice must come from a boldness of the mind – that is, not adapting to external orders of the world but rather adapting that information to that which is internal. Although we share the singular great cosmic energy that makes up every organic material, it is all differentiated – nothing or no one is the same. We spoke together and for them it seemed to be one of the first times they too had reflected together on their rapport, their interaction, what is going on.

Trever Hagen: So how did you two meet? How did you start working together?

Kim Gordon: We met through our mutual friend Francesca Gabbiani, who has a studio here in Los Angeles.

TH: Did you start rehearsing together when you met? Was there something that brought you together?

DC: Because.... let's change direction. Because really what I enjoyed and what I think is making me think strong things [about this performance] — is that we don't really rehearse, which is totally unusual for a dancer. It was very organic and spontaneous. We have this friend, she had an exhibition and she kind of invited, or proposed [this duo with Kim]. So I thought: ‘What could be strong?’ And I wouldn't even say it was to collaborate but just to make something together.

Anyway we said yes. So Kim invited me to her place to make a kind of try of something, like informally in a living room. And then she was starting to plug in the things [guitars and cables] and I was warming up. I was like ‘Maybe she already started?’ But then very quickly we went into something much more physical, to kind of avoid the imagery of the “player playing and the dancer dancing” because what I also love from Kim is the body and the voice. The voice is a body. It is very enchanting – talking and singing. It is it’s own territory – choreographical territory. So I was very interested by that. Then we did some very physical stuff – but then after 20 minutes I was tired so I went to the kitchen to have a drink. When I came back she was unplugging the stuff. [Kim laughs]. Because as a dancer you start at 10am and end at 6pm. Long rehearsals. Then I said, ‘So for me it is great.’ I really loved that. Because it really re-questions what the work is, especially when the work is improvisation. In dance we have a tendency to prepare improvisation a lot so it is a start of a writing, in a way. What I liked with Kim and what she did, in way was meaning like: ‘If we are going to improvise we have to be scared, we have to be fragile.’ The biggest gift we can give to an audience is to be in front of them like that. It is going to be unique; it is going to be fragile, adventurous. This is improvisation. So I really loved that and since then I have been trying to keep that. We don't see each other a lot so we meet and do that. So it is still super fragile. I know some ways of Kim's body but I don't have a memory of the show. So we don't re-do the show. We meet and "do that thing" assuming that it can be fragile. That's my experience.

TH: Did you have any different take away for the first rehearsal than perhaps what you were expecting?

KG: Not really. We had talked about contact improvisation before because I had done a workshop with Steve Paxton when I first went to New York. One of the reasons I moved to New York wasn't just to do visual arts but also I used to get Dance Magazine, I read about Yvonne Rainer and the Judson Church group [Judson Dance Theater] and I was like how can dance be a phenomenon? That was all very interesting to me – interdisciplinary, the way they were working, and so I was always interested in that.

TH: Was Paxton a mutual reference for you both?

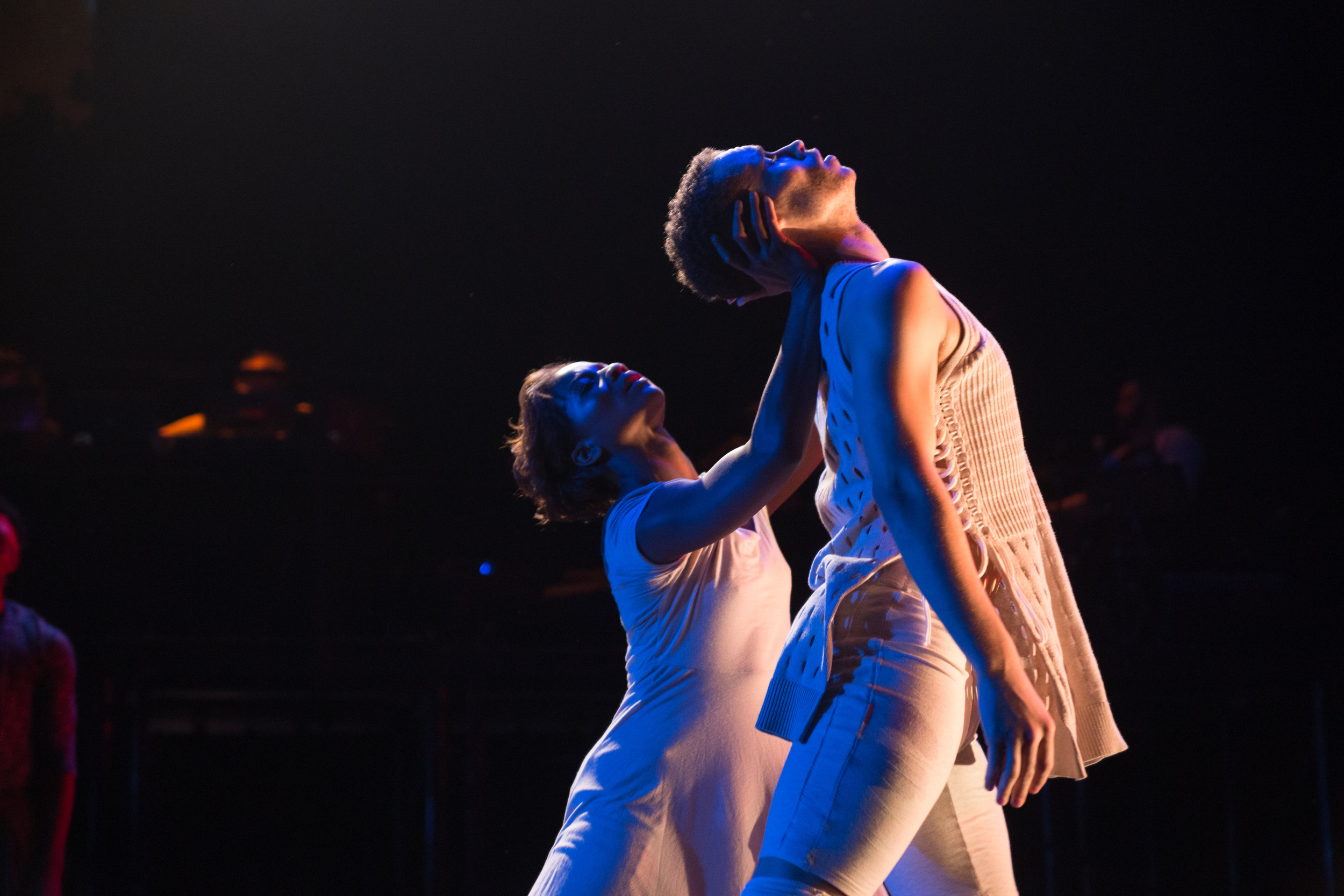

KG: We had talked about him, yes. I did one other collaboration with this visual artist Nick Mauss – he's a visual artist who is very into dance. He had done something with the Northern Ballet Company and asked me and Juliana Huxtable, a trans performance artist, to interact with the music. And I ended up moving into their space a bit so I got a sense of that and it was really fun.

TH: Have you been able to incorporate any of these aspects of balance, touch or momentum into musical worlds?

KG: I guess I have always done that. In Sonic Youth there was always a couple of songs, like “Expressway [to your skull]” where I would stand on the bass, I had a big one. The thing about electrical instruments is that they respond to movement, they are very visceral. You can affect the sound by the way you move. Playing guitar and those gestures. So I was very aware of that. And now, I have this duo – Body/Head, it is two guitars and all improvised. I have always liked to somehow take my guitar and interact with the structure of the space. You know like I'd love to make a film or do a performance under a freeway, you know with like using the cement like a guitar slide and playing with the architecture.

TH: It was interesting to see your performance in such a small room, this gallery space - you have both performed on iconic stages all over the world. Each of these spaces seems to afford a different property. Is there anything you enjoy about these smaller spaces in contrast to larger stages? Or underneath a bridge?

KG: Well it is just different being surrounded by the audience, right? Being with them and not on a stage.

DC: These last two years in New York I did a lot of stage-based frontality. The first piece I did was a duet with Boris Charmatz we did this piece just after the conservatory. We did it to experiment because at conservatory you learn that a gesture has to be done for a direction, you learn that when you land from a jump the audience shouldn't hear any noise, if you are out of breath the audience shouldn't hear that, etc. etc. So this is one relation to an audience in traditional dance. But then we started to say – ‘No we have to assume that an arm has a weight and that weight makes noise. And we have to assume that a movement can be seen from there and also from there. And we have to assume the context changes the meaning of the movement.’ If you put your hand like this [out-stretched before your chest] and you are near an apple tree, it is to grab an apple. But if a door is there, it is to welcome someone. If it is after a competition then perhaps it is there to make a high-5. So the context is painting the dance. This is why I like these dances: it leaves a lot of room for people to tell themselves their story free of the body and gestures. Being so permeable to the context.

Regarding the gallery performance with Kim, I must say that I kind of liked being close to the audience. I really focused on Kim and the space she designs – herself with her moves and herself with the cables, that's the space for me. I don't really mind about 'Do I attribute a gesture to a direction?' – I am not this way at all. We are more like: ‘What kind of dance can also be the right reaction to what Kim is proposing?’ And for example when the dance is super clean and super designed and super clear, even like super technical – it creates something together which is much stronger than when I go into my own crazy gestures or whatever. Those are just from the experiences we had so far.

KG: Yeah you can't really think about the ends. It is hard to look at yourself because it can take you out of what you are doing. But in the past – playing music on a stage – it is fun to break that wall and go into the audience. They don't expect it. In a way, one thing I always thought was interesting was that the sound on stage is always different than the sound in front of the PA. So the audience never feels that same surround-thing that you do. But you are basically plugging into the technology of the club, and so that is kind of between you and the audience in some way. It is not exactly two different worlds, but it is two different experiences. [On stage] doesn't sound as perfect. Up front you have someone mixing the sound and on stage it is messier. Maybe you don't hear everything – it truly is more in your head or in your body.

DC: Of course it is music, but she is really a performer – with a very special way. She works with the body, with some experiences with different practices. So it is really a performance or a duet. I like that because we never had those questions. I co-teach a class with David Rosenboom and we have 12 composers, 12 dancers together in the room and we are questioning all of those relations between music and dance. How music can be the space for the dance. How music can be the color for the dance. How the dance can be so noisy you don't listen to the music anymore. All of those things. Which there are not those questions here [with Kim]. Because it is really like two performers together (there is the guitar and there is the voice), but really it is how you offer your partner balance. How she trusts you, how she reacts to that, how she takes the lead and brings you somewhere.

TH: It is very delicate negotiations it seems. Is there anything in the space or in realtime that is emerging – like a rule or a challenge – that you don't pursue?

Marie-Agnès Gillot

DC: What really excites me about this project, about this duet, is when you dance with someone and you are surprised by their reaction you have proposed. For example I am doing this duet with Marie-Agnès Gillot – she is like the l'étoile dancer of the Paris Opera but kind of a crazy-amazing artist. And when I bring her into a direction she twists it into something else. [Kim and I] have the same – when I twist Kim sometimes – I don't know, a lift or going to the floor – she might follow but she might add something to it that transforms it. For having been dancing with many different partners – what I like here is the craziness of the reactions. The freeness. Like, I initiate something and then suddenly I have a mic there – it is complex, unpredictable and that's the best. That makes it a dance piece, a performance piece, for me.

TH: It is in that improvisational spirit of always supporting—

DC: —and also trusting someone you don't know. Because that's how you accept to give your weight to someone that puts you in danger. "Going out of balance", we say, is the beginning of the dance. Because going out of your balance will make you travel in that space with a temporality. Changing the space, so it is choreography. That's some stuff you can think of in the creation process – but it can take a very long time to be able to do so with your partner. To bring her into some directions that she really has to trust you with. But with us, it was really immediate.

TH: Indeed this rapport can be very difficult actually to establish with someone in a real way, not just performative.

KG: [Laughing] I have never danced with anyone – (except a noise piece I did with my niece). But what I wanted to ask you [Dimitri]: How do you teach performance? You can teach dance? How do you teach dancers to have a presence? Or projection?

DC: For example, talking about the 'présence', when I arrived at CalArts, because of the teaching they had, the présence was like super focused on the outside. Kind of showing présence. It puts your body super up and in front. You know? And then I recruited this guy, who is a Trisha Brown dancer – and through body-work he changed the présence of the dancers. To make your body conscious of the weight of the body, of the fact that with arm – to go from here to there – you don't have use energy, just relax the weight will do the work. So then suddenly, these dancers started to be simpler, not playing anything. And then you have this space, you can make decisions. So this question of présence is really related to the body. The posture and the energy.

TH: Kim is there anything you've learned about présence?

KG: Well one thing that has surprised me… sometimes my lower back hurts – that was my trepidation – but the next day after our performance I felt great. And I find that when I just get to move around that is the best thing for my body.

TH: Was there something with movement creatively that you have found different than with other art forms or media. Was there an idea you were exploring in movement you couldn't find elsewhere?

KG: It was pretty much how I thought it would be. I mean it is hard to improv for like 30 minutes. Even for a musician. Bill [Nace] and I do all the time but sometimes it is harder to get past the 30-minute mark. There is just a lot that I have learned from playing with Bill that has been helpful in any improv situation. Also this [performance]. There are times when both of you don't have to be playing or not move... it is different from like ‘oh here is a solo’ – it is not that. It is part of the range of dynamics that can be used.

DC: What I love, when I think about it, is the way Kim is doing the things. Sometimes I am too over-invested. What I really like is very strong and related to the présence thing and to the energy – sometimes she is going to be with the guitar and then she will be over there... like, ‘Is she performing?’ She is totally into it, but with distance. So this kind of présence and energy is incredible. She is so strong. We have rehearsed once and performed once so it is still fresh and we don't know what it is. But it is great. I love that because it is totally unusual. Like in a living room or in front of people – same thing. Being super busy but not to show. Being busy, but only to do the stuff [the tasks of working with objects]. And that is super strong. And that is something I think about – how do you translate that into dance? That is something very particular that you [Kim] have.

TH: Are you thinking of anything in particular or just going in with your guitar?

KG: Well I am kind of thinking of two things – what is going on with the sound, what is going on physically. Sometimes I think maybe I should bring in some more sound but that is just very intuitive.

TH: How does it feel in the performance space when you put your guitar down?

KG: Yeah it is probably more awkward. Having the guitar and microphone, the sound part that I am responsible for, gives me a way to not feel self-concisous about ‘I am doing a dance.’ I always have to trick myself so as to not feel self-consicous.

DC: I do not feel it honestly that you are two different bodies. But listening to you, then, it is conscious to me that you have double the amount of work. Running the music and dancing. Sometimes I feel like we are together but you are busy doing something else – it is great, I love it. We are together but we are not really together. But we really are together.

KG: I don't think of the music as music but more like a texture or some other aspect, like an environment we are moving around in. And then trying to think spatially a little bit.

TH: Do you ever touch the guitar, Dimitri? How do you like working with an object like this?

DC: Same thing – I have no questions [like] ‘Does it change my stance?’ It is there. I was surprised because I didn't know how Kim was considering the guitar as 'her object'.

KG: I probably shouldn't be using my favorite guitar actually – because usually I know how far I can go with it without destroying it. I think I could be freer if it wasn't my favorite guitar. [laughs]

DC: You know sometimes it is great to go easily from one thing to the other on some points, which are really big questions in the art. In classes you could spend a semester studying how you appropriate an object which is not yours by being invited in this context. In this context, it is not. The nature of the guitar in our performance is really changing.. .sometimes it is your [Kim’s] instrument, sometimes it is an object that makes things more complicated, sometimes when you put it somewhere it opens a territory, it is kind of a set up for a new space.

KG: And the guitar is so loaded with gestures, like the heroic gestures that male rock guitarists do. I wrote a piece on that, I have a performance based on that. [laughs]

TH: For sure and when you see this object thrown on the ground, it is still loaded with these gestures, those discourses but in a vulnerable and almost useless way. Or disregarded.

KG: People obsess and fetish over guitars...

TH: So it sounds like everything that you are up to in spatialities, discourse, repertoire or things you've learned is kind of “out the window”?

KG: It is and it isn't. Just as I bring whatever I have learned through everything I've done, so does Dimitri. You have your vocabulary – things that you know.

DC: I think it is the one [performance] where I bring the most of my experience. If you don't then you can't just meet 20 minutes. You bring your whole culture, life and experience. That is something I couldn't do with anyone else. We bring a lot in a very short time. This project to me is very special. We have done it very few times. We could do it all the time – in Paris [for example] – but we don't. So it keeps it very very special. I have it in mind not every day but I think about Kim a lot and what is this thing – but we concretely do it very few times. She is the opposite of the shows that are touring that I dance with. I do 4 shows in New York and then fly here and forget about it. This is the opposite. The presénce of the show is in the everyday life but the reality of the show is kind of never.

And so we return to the quotidian: an investment in the richness of resources to be found in the “variety of your everyday life,” as Dimitri says. What might that return look like? It seems it would be to re-associate présence not necessarily with performativity nor even with habit or routine, but with how you adapt the outer world to your inner world in a way that effortlessly amplifies the power of gesture. The power of one’s voice, in other words. Présence in this everyday manner focuses and communicates your entire history into an expression, sound or movement – something that is undeniably yours, for which the only school to learn from is located within.

Follow Liquid Music for updates and announcements:

Instagram: @LiquidMusicSeries

Facebook: facebook.com/SPCOLiquidMusic

Twitter: @LiquidMusicSPCO

Follow Kim Gordon & Dimitri Chamblas:

Kim Gordon

Instagram: @kimletgordon

Twitter: @KimletGordon

Dimitri Chamblas

Instagram: @dimitrichamblas

Website: https://www.dimitrichamblas.com/